|

I am on a mission to capture every fish species in the Great Lakes. See my progress here

AuthorBrian Roth ArchivesCategories |

Back to Blog

Local life, local rivers..local pirates?10/30/2020 COVID-19 put a damper on pretty much all of my travel plans. My hope was to have at least 100 species in the books by now. But I’m forging on. The Lansing area has a number of wadable streams that are great for electrofishing. The Red Cedar River runs right through MSU’s campus, and the section that runs through campus is electrofished pretty commonly for classes. There are other locations with public access upstream from campus that I’ve never electrofished, and this is a pretty good time (when I can get away) to explore. Just north of town is the Looking Glass River. The Looking Glass is slightly smaller but offers a pretty good contrast to the Red Cedar. The Red Cedar runs through a mosaic of Agriculture, Forest, and Urban landscapes, with pretty diverse substrates. The Looking Glass is pretty much all Ag, and rocky areas are pretty rare. So I shocked both! I’ve concentrated most of my effort on the Looking Glass because colleague Mark Stephens has captured Pirate Perch there. And I want to catch a Pirate Perch. Pirate perch are perhaps the weirdest fish we have in the Great Lakes region. On the surface, it's just a small charcoal-black fish with a big mouth. However, it represents an evolutionary intermediate between soft-rayed fishes (like salmon and minnows) and spiny-rayed fishes (like bass and perch). It is in the Order Percopsiformes, with another weird fish, the Trout Perch. But that’s not the weird part about the Pirate Perch. Its *ahem* vent is under its chin. You know that saying “Don’t @#$& where you eat?” Well, Pirate Perch don’t have that apparent luxury. Some comedian then gave this species its scientific name: Aphredoderus sayanus. Oddly enough, the species name (sayanus) is actually in reference to Entomologist Thomas Say, and its genus translates from Greek to ‘Excrement throat’. What in the holy hell is going on here. Either way, I’ve caught a bunch of species in the Red Cedar and Looking Glass. To be exact, I captured five species so far in the Red Cedar (from one trip), and 10 from the Looking Glass (in two trips). One of those species from the Looking Glass is, you guessed it, ol’ shitneck itself. I got a Pirate Perch on Oct 29 with the help of my graduate student Jake Sawecki. He saw it pop up and immediately knew it was weird. We only caught one, so I won’t be able to use this species for ID in my Ichthyology class just yet as I’d like to get at least ten specimens before I introduce them to the class. But I’ll be back.

1 Comment

Read More

Back to Blog

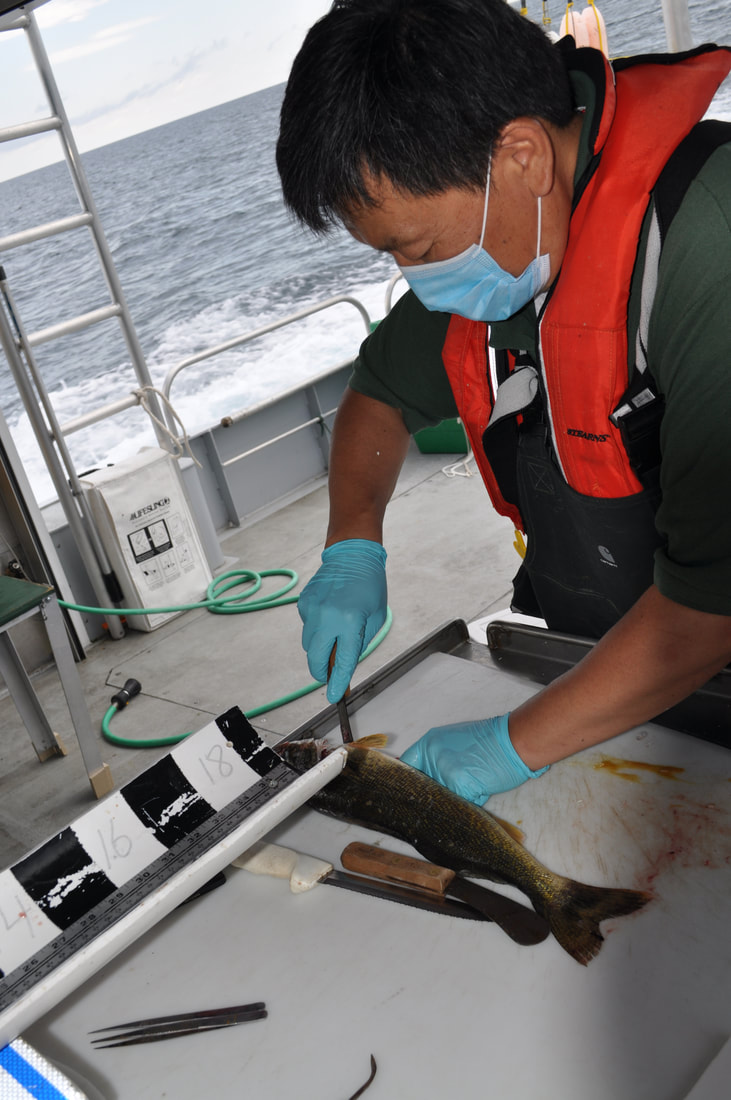

So much for spring surveys10/22/2020 COVID-19 has disrupted many aspects of everyday life. One that may have flown under the radar was the cancellation of spring fish population surveys conducted by management agencies around the country. These surveys are responsible for assessing populations of recreationally, commercially, and culturally-important species. Here in the Great Lakes, one of the most important of these surveys are those conducted for Lake Trout. Lake Trout surveys usually occur in May or June, depending on lake and latitude. For my sabbatical, I had hoped to accompany management agencies to on some of these sampling trips, as they represent the best chance I’ll get to capture species only found in “The Big Water”. So imagine it’s now late July, and I’m heading up to Alpena to go out with the Michigan DNR on Lake Huron. I am so grateful to finally be able to get out of the house and get on the water. I was invited by colleague and collaborator Ji He, a Fisheries Biologist with the MDNR. Ji is an expert on Lake Trout in Lake Huron, and has been on the staff at the Alpena Fisheries Research Station for a LONG time.  Leaving Alpena on the R/V Tanner Leaving Alpena on the R/V Tanner So I hauled my ass up to Alpena, leaving the house at 3:30 in the morning to get up there by 7. Oscoda is a LONG way from Alpena, but at that time DNR personnel were unable to stay overnight away from Alpena. So I spoke with Ji as we headed to Oscoda at 18kts on the R/V Tanner to retrieve standardized gillnets. That is to say, it was LOUD. REALLY loud. I may or may not have only heard somewhere between 30-75% of what Ji was saying. I really don’t know, because like I said--it was loud. While Lake Trout are doing monumentally better than they were historically, the question remains whether they should be doing better than they are. Further, even though we’ve been conducting these surveys for 30 plus years, we have almost no idea how effective or efficient our methods are. Ji and I talked at length (I think) about how to best determine whether gillnets represent an accurate depiction of Lake Trout abundance, even in a relative sense. The water is now so clear on Lake Huron, there is a chance that the ability of gillnets to capture Lake Trout has declined through time. Think about it—if you see a giant spiderweb in your way as you’re strolling through the woods, you generally don’t walk into it. But if it’s really foggy, you might stand a better chance of ending up getting real comfortable with an eight-legged friend. Our catches were low. The crew said usually they’ll handle a couple hundred Lake Trout, along with dozens of burbot, Lake Whitefish, Round Whitefish (called Menominee locally) and various other deepwater species. We maybe caught a dozen Lake Trout in 4000ft of gillnet. We actually ended up catching more Walleye than Lake Trout. I was able to add three species to my list: Lake Trout, Round Whitefish and Coho Salmon. Such is the perils of conducting spring surveys in mid-summer. Nonetheless, we were able to get some stomachs for the Predator Diet Project, and I got to spend a day out on the water. A big thank you goes out to Ji He, Captain Bill Wellenkamp, and the rest of the R/V Tanner crew. Hopefully I’ll be able to go again in spring of 2021. And by that, I mean actual Spring.

Back to Blog

An Introduction10/22/2020 Nobody knows how many fish species are in the Great Lakes region.

But I plan to change that. I am a fish biologist at Michigan State University , and I will spend the next year searching for every one documented in the region. That’s 179 species of fish. I will determine which are still here, which have disappeared and if new ones have found their way here and have yet to be documented. Some species, like the bluegill, are found just about everywhere in the region. Others, like the spotted gar, are so rare I can count where they could be on one hand. Still others are secretive and enigmatic, like the pirate perch whose anus lies directly below its mouth (as a side note, the scientific name for this species is sayanus). My quest to capture every species is much more than (ahem) a fishing expedition. Fish are a wet, slimy version of the proverbial canary in the coal mine. They are bellwethers for environmental problems that arise from the activities of people on the land. Their number and type are powerful indicators of the health of the Great Lakes. One-third of the 100 million humans in the Great Lakes region get their drinking water directly from the lakes. Many others obtain water from wells deep within the ground. With every toilet flush, load of laundry and pot of boiled pasta, this water weaves its way back into the Great Lakes to eventually be used by humans again. But first, fish will have a turn to swim, breathe, and yes, go to the bathroom. Perhaps we should pay more attention to what fish are doing. The species of fish that live in the Great Lakes and its surrounding waters tell a story where people almost always play the villain. People whose lives revolve around fish are storytellers, and part of my plan is to listen to tribes, anglers, commercial fishers, and academics to help provide the prologue for how changes in fish affect us all. Although us people tend to look at the Great Lakes by standing on its many shores, my goal is to view the Great Lakes from inside out. With a fish-eye lens, shall we say. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed